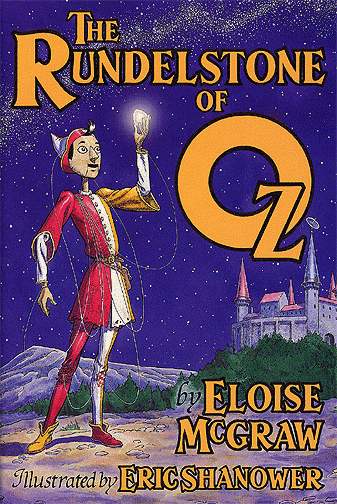

The Rundelstone of Oz, by Royal Historian of Oz Eloise McGraw, opens on a distinctly unusual note. Ozma is trying to do her royal duties. (Really. Control your shock.) Of course, these duties include taking a moment to sip tea with two of her royal ladies-in-waiting, but everyone has to start showing responsibility somewhere. It took me a moment to realize that this was the first time, in 100 years of official Oz books, that any of these ladies-in-waiting had ever been identified. I rather wonder how some of those nobles actually feel about some of the mortal girls—Dorothy, Betsy Bobbin and Troy—who displaced them in Ozma’s affection and in courtly ranks, but if any of them voiced concerns, the Royal Historians of Oz placed a discreet veil over their remarks.

Fortunately, before the book gets lost in tea parties and court intrigues, it switches over to something considerably more fun: talking puppets.

The puppets turn out to be part of a rather ramshackle traveling show, led by a rather nasty stage manager who may, or may not, Have a Past. Whatever this mysterious past, the stage manager makes one major error: he brings the puppet show to the town and castle of one Whitherd, who like seemingly everybody else in Oz is happily breaking Ozma’s “Do Not Practice Magic Without My Permission” Law.

(Seriously, ridiculous speed limits get more respect. I can’t help wondering why Ozma even bothers with the law given that nobody seems to want to follow it, which is really not surprising in a land bursting with magic.)

This decision turns out to be dreadful for the puppets, and particularly for Poco, their flutist. When he awakes, the Whitherd casually explains that the other puppets abandoned him, and a forlorn Poco agrees to stay around as a servant—and a subject for the Whitherd’s experiments. It does not, however, take Poco too long to realize that something is going on, and to realize that just maybe, the other puppets never really left at all.

In an earlier post, someone complained that The Rundelstone of Oz doesn’t feel very Oz-y. In the sense of not featuring the beloved characters from Baum’s books, except in the very beginning and the very end, and in the sense of suddenly introducing a group of human courtiers and a rather suspicious dearth of talking animals (not to give too much away), this is true. And the book also strangely fails to feature, or even mention, the traditional party at the end of nearly every book—aside from a discussion of eventually having a puppet show at the Emerald City in the vague future, but that’s not quite the same thing.

The lack of talking animals, as I’ve hinted, turns out to be a major clue for alert readers (I’m mentioning it here because I think adults and older children will easily guess), even if McGraw hastily attempts to explain the clue away before readers can get too suspicious by explaining that although all animals in Oz can talk, most choose not to talk very much. The problem is, this applies, as far as I can tell, to only one animal in the entire series (Toto). Otherwise, Oz appears to be filled with animals that can’t seem to stop talking, so I’m not sure how well this excuse distracts readers (it made me more suspicious). And given that Poco had spent much of his life with two talking donkeys, it seems to me that he should have had the same suspicions much faster than he did. But let us be kind: perhaps he was a bit distracted by getting kidnapped and transformed and losing his friends. It’s understandable.

But if the lack of talking animals is a distraction, The Rundelstone of Oz is entirely different than the rest of the canon in several major respects. First, rather than the usual Oz plot that forced characters to head out to explore the strange and fantastic little places of Oz and its surrounding countries, for whatever reason, The Rundelstone of Oz, the initial tea party aside, takes place in only one location: the Whitherd’s home. And the book’s tension neatly reverses the usual goal of trying to get home, or get a home in the Emerald City: the trapped Poco is desperately trying to leave. He doesn’t have a permanent home outside of his little traveling wagon, but he doesn’t want one. Traveling, he assures his new friend Rolly, is the life.

Only one or two characters have ever expressed this philosophy before (the Shaggy Man and, arguably, the Scarecrow in some of the earlier Oz books) and even they gratefully accepted permanent homes to return to between wanderings. It’s a major switch, especially considering that the series began with a child desperate to return home. True, the closest thing Poco has to a family—the other puppets —travel with him in the wagon, so in a sense, his desperation to find and rescue his puppet friends continues that theme. But otherwise, this marks one of the greatest departures from the Oz series so far.

Perhaps something happened in the one hundred years between the The Wonderful Wizard of Oz and The Rundelstone of Oz, where authors could no longer take the same comfort in tales featuring young children setting out on their own for adventures, accompanied only by strange creatures of straw and tin and talking animals. I’d like to think not, especially since I have a deep set suspicion of nostalgia, but I can’t help but notice the way cars line up to pick children up from the local middle school, the tales of kidnapping, the fears that children are growing up too fast. I don’t know how much of this, if any, was in Eloise McGraw’s mind as she wrote a tale where the protagonist wants, above all, to escape a secure house and job and run off to perform plays and explore strange new lands. But perhaps some backlash is reflected in this tale, where for once, instead of trying to escape zany and terrifying adventures for the safety of home, a puppet is trying to escape a banal, dull work environment for something seemingly far less safe—even as the banal, dull yet seemingly safe environment turns out to be not so safe after all.

But for all this, I can’t quite agree that this isn’t an Oz-y book. It contains all of the delightful Oz elements: magic, transformation, things that shouldn’t be able to talk that can, even a couple of little kingdoms who in classic Oz style have messed up with magic. And despite what might seem like shades of Pinocchio, this is a tale of non humans who are delighted, proud and content to remain puppets, just as the Scarecrow firmly believes that his straw stuffing is better than the meat of real humans. It’s another reminder that in Oz, people and creatures can be anything they wish to be, and that in Oz, anything can happen, even to puppets who just want to travel and play a flute.

The Rundelstone of Oz was the last Oz book to be written by the official Royal Historians of Oz, and unless someone can persuade Lauren McGraw to write another, will be the last, if most certainly not the last Oz book. Fittingly, it appeared in 2001, a little over a century after The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, wrapping up a marvelous one hundred years of Oz explorations.

Of course, by then, some people had taken a decidedly different, and more jaundiced, look at Oz. Coming up soon.

Mari Ness is firmly of the belief that puppets are better off singing and dancing than attempting to be butlers. She lives in central Florida.

Hi Mari–

Enjoying your Oz rundown. Are you covering Paradox and Living House? I’d love to hear your takes on them.

Best wishes!

Edward Einhorn

Not in the immediate future, at least. The current plan is to cover the Maguire books, have a quick detour for a special Baum Christmas post (you can probably guess the book) and then leaving Oz entirely and heading on to that other fantasy series featuring a talking lion. We also have to see how long Tor.com continues to indulge me with my various fantasy obsessions :)

Narnia???? Oh yes, please!!

(And sorry to not have anything else to contribute, but seeing as my knowledge of the Oz books is rather – shall we say, limited – I usually just choose to read these fun Oz posts and not prove my ignorance by opening my big mouth. Er, fingers. Whatever. I really have enjoyed this series though, just in lurkey silence!)

Just to let you know, Mari, that “Ozzy” has been a perfectly acceptable word in Oz circles since it first appeared in the introduction of “Ozma of Oz” back in 1907. So there’s no need for the clunkier (to me) construction of Oz-y.

And please keep up the good work. As a long time Oz fan, it’s refreshing to read your opinions and get some new insights into the books. But a detour to Narnia would be a wonderful trip, too!

I could keep reading these Oz reviews for as long as people keep writing Oz books — I only wish that more of them were in print! It’s frustrating to read about an Shanower edition I can’t get.

@gpmorrow — Rundelstone of Oz is in print and easily available from various online outlets, and possibly from a local library if you ask really nicely. (My own local library didn’t have it and didn’t have the funds to purchase it, but was able to locate the book through interlibrary loan–you might want to check, since I assume that varies from library to library.) The difficult to locate book was Rachel Cosgrove’s Wicked Witch of Oz, which is why I didn’t review it here.

@gpmorrow — I would like to recommend a new series of children’s books based on Baum’s Wizard of Oz books. The Royal Magician of Oz Trilogy features Magician of Oz (volume 1), about young Jamie Diggs, the great-grandson of the original Wizard and his discovery of his magical heritage as he travels to Oz to battle the Army of the Trees and the Marauding Morels alongside his new friend, Dorothy.

In Shadow Demon of Oz (volume 2), Jamie Diggs returns to Oz with his best friend Buddy at the command of Princess Ozma in order to battle an ancient Evil from long ago and save the citizens of Mount Hyup.

Family of Oz (volume 3: due out in Feb. 2010) completes the trilogy as Jamie Diggs, now the new Royal Magician of Oz brings his family along for a wonderful journey through the Land of Oz as he battles Cobbler the Dog and teaches Princess Ozma the true meaning of family and Love.

Information about these wonderful books for children and the Royal Liaison to Princess Ozma, who is the author, can be found through Google.

@james C. Wallace III —

You’ve been asked not to do this.

Please, again, remember, this is Tor.com’s playground, not yours, not mine. It is not a place for pimping your own work.

@james C. Wallace III–as Mari says, these conversation threads are not the place for commercials or relentless self-promotion. Speaking on behalf of Tor.com, you are welcome to contribute to the discussion, but if you continue to hijack the conversation and harass our bloggers, you will be blocked by a moderator.

I would offer my apologies for this. It reminds me that I seem to lose track of where I’m at… from time to time. A symptom of the madness, I suppose.

Its not my intention to be spam, however, as a courtesy to Tor.com, I am removing Tor.com from my blog watch list.

Out of sight, out of mind… if you will.

Once again, I apologize for the inconvenience.

James C. Wallace II

Responding to gpmorrow:

I’m not sure which Oz books I’ve worked on you can’t locate. What are you having problems finding? I believe everything is in print except for Invisible Inzi of Oz and Paradox in Oz. You can find used copies of both online in the secondary market, although Inzi might run a bit pricey. Even The Wicked Witch of Oz is in print–the Oz Club should have plenty of copies sitting in a warehouse somewhere–just that the Oz Club can’t currently handle fulfilling orders for its publications. (Aside to Mari: Sorry about that. If you still want to read it, let me know–we can figure something out.) Some items that aren’t strictly Oz books, such as most of the volumes of Oz-story, are out of print, but I periodically see volumes of Oz-story offered on the secondary market at reasonable prices.

Just discovered this blog and I’m absolutely LOVING the reviews. “Ozma Fail” has just entered my own personal lexicon.

@gpmorrow and ericshanower: I’m not sure about the books on the used market, but Oz-Story is indeed pretty easy to pick up through the Amazon Marketplace or eBay, at very reasonable prices if you look hard enough. Just last year, I assembled a mint condition set of all six volumes for around $10 a pop. “Rundlestone” in particular is contained in its entirity in Volume 6.

i always felt (and may have said so when you posted about it–i am finding all these posts about post-famous 40 books long long long after you wrote about them and long after i read about the first 40) that something similar could be said of Rinkitink in Oz–that it seemed for all the world like a non-Oz book that had Oz tacked on to the ending to turn it into an Oz book. maybe you said exactly the same thing, come to think of it–it’s not exactly subtle. otoh, it’s a book i like very much, or at least i liked it very much when i read it, which is also a long long time ago.